Biography

The Eighth United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon: A Brief Biography

by Jean Krasno

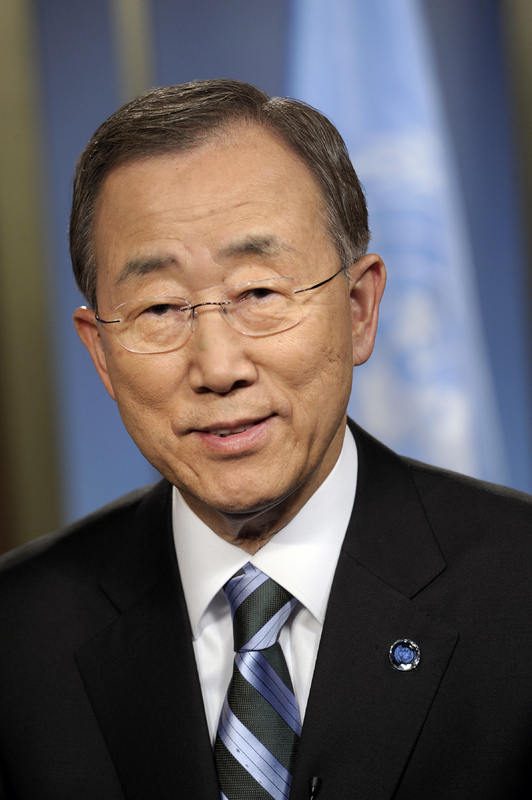

Photo Portrait of Ban Ki-moon

The United Nations’ eighth Secretary-General, Ban Ki-moon, eldest of six children, was born on June 13, 1944, in a small village called Eum-seong near the center of the Republic of Korea. In 1944, one year before the end of World War II, Korea was still under colonial occupation by Japan, an experience that still reverberates within the Korean Peninsula. In 1950, only a few years after emerging from Japanese occupation, and when Ban Ki-moon was just six years old, the Korean War broke out between the north and south, the first major war since the end of World War II. At the outbreak of the conflict, his family fled to the mountains. Ban explains that they were very hungry and he “could see the fighter jets bombing the towns and cities nearby.”1 Residing in the southern part of the Korean peninsula, Ban lived through a period of extreme violence, devastation, destruction, and fear. He recalls when the UN-authorized troops from many countries around the world arrived to defend the south, it marked an important time in his young life. “Without the United Nations, first of all, I would not be standing here as Secretary-General. . . . The flag of the United Nations, to all of us including myself, was a beacon of hope.”2

Not only did the UN authorize the military defense of the Republic of Korea, but during the conflict and after the hostilities ended, the UN also brought humanitarian relief through UNICEF, UNESCO, and the UN Korean Reconstruction Agency. When the armistice agreement was signed—Ban being just nine years old at the time—he recalls, “I thought about what I should do in the future for my country. I thought that to be a public servant and particularly a diplomat is the way I can contribute.”3 He considers himself a child of the United Nations. In looking back, Ban realizes part of why he decided to go into the field of diplomacy was his own experience with the UN’s role in Korea. “Once a child of the UN, this child is now the Secretary-General of the United Nations.”4

In Korea at the time, the dominant philosophy was Confucianism which taught that after the age of seven, boys and girls should not attend the same school. It was then Ban became aware, both at home and at school, that women had “no recognition of their social status.”5 He explains how he found this discrimination very unfair and, when asked in middle school to write an essay to commemorate the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, he chose to write on women’s rights, winning a prize not only in his school, but citywide.6 Recognition for his writing skills came early and in 1956, at age twelve, he was selected by his fellow students to write a letter to then UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld expressing their concerns over the Soviet Union’s suppression of the Hungarian uprising.7 This sense of support for human rights, but especially women’s rights, stayed with him, becoming a focus of his work as Secretary-General and the creation of UN Women fell under his watch.

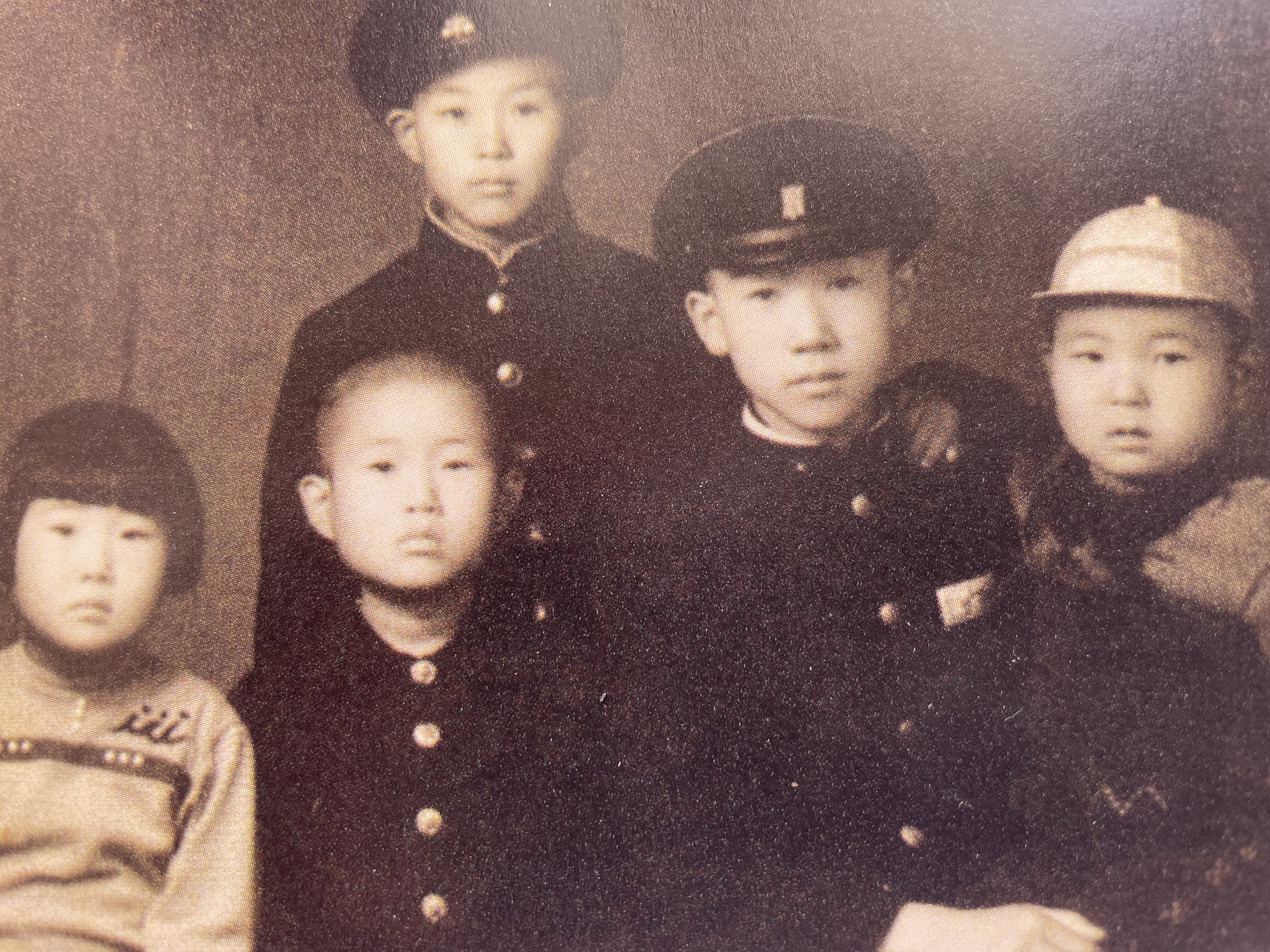

Ban Ki-moon as a Youth

As a senior in high school in 1962, Ban Ki-moon, along with several other students from fourteen countries, was invited by the American Red Cross to visit the United States. They traveled to several American cities and then finally to Washington, D.C. On August 10, 1962, the students were received by then President John F. Kennedy. Ban recalls how thrilling this experience was, and that the president encouraged them all to go into diplomacy and extend a helping hand to others.8 Ban went on to earn his bachelor’s degree in international relations in 1970 at Seoul National University and, that same year, joined the South Korean foreign ministry with his first assignment in India. A few years later, he became the Director of the United Nations Office in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Taking a short leave of absence, Ban completed a master’s degree in public administration, coincidentally, from the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard in 1985.9 He served in the foreign ministry for some 30 years with postings in several countries, including the United States and Austria. As ambassador to Austria, he became chairperson of the preparatory commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty Organization, gaining in-depth knowledge of nuclear issues.

Though Ban Ki-moon rose through the ranks in the foreign ministry, he recalls an incident in 2001 which cost him his job as vice foreign minister. South Korean President Kim Dae-jung, a Nobel Peace Laureate awarded for his work on improving relations with the North, made a state visit to the United States for a summit meeting with President George W. Bush. The summit, which was televised, did not go well, as Ban describes. “The summit meeting went badly. . . . There was a big scandal when President Bush put his hand on [President Kim’s] shoulder and called him, ‘this man.’ It was not respectful.”10 President Bush did not even refer to him as President Kim, as if he had forgotten his name. This became a big issue at home. “In addition, President Bush had announced that he would cancel the ABM Treaty with Russia which was not received well in South Korea.”11 Kim Dae-jung had supported the bilateral treaty and was taken by surprise when President Bush announced U.S. withdrawal. It became a major political embarrassment at home and President Kim decided to dismiss Ban who had been part of the team organizing the summit.12 “I took responsibility as the vice foreign minister. I was just fired without any job. I just became a civilian.”13

However, this incident evolved into a beneficial opportunity. Han Seung Soo of South Korea, who had just been elected by the members to take the position of president of the UN General Assembly, decided to name Ban Ki-moon as his chief of staff. With a prestigious office at UN headquarters, this new position enabled him to become more visible to the United Nations community and to the world. A few years later in 2004, Ban became foreign minister, and on October 13, 2006, he was elected as the eighth United Nations Secretary-General. He was the second Secretary-General to be elected from Asia, the first being U Thant of Burma, what is now called Myanmar. Ban was selected two- and one-half months before taking office which gave him more time to prepare for the position. His predecessor, Kofi Annan, was chosen only two weeks before he took office ten years prior.

One of his priorities upon taking up the helm at the United Nations was to focus on climate change. Within his first year in 2007, Ban visited Antarctica and made this statement:

I am here today to observe the impact of global warming. To see for myself and learn all I can. We joke among ourselves that we are on an “Eco-tour”, but I am not here as a tourist but as a messenger of early warning.

What we saw today was extraordinarily beautiful. These dramatic landscapes are rare and wonderful, but it is deeply disturbing as well. We can clearly see this world changing. The ice is melting far faster than we think.

All this may be gone, and not in the distant future, unless we act, together, now.14

Ban wanted to sound the alarm on the issue of climate change. To draw more attention to this crisis, he also visited numerous places around the world to highlight the challenges each region faced due to climate change. He traveled to the Arctic three times, where the ice is quickly melting; the Amazon river basin, where the rainforest is burning; the Aral Sea, which used to be a sea but is now a dry, flat salt bed; and he flew over Lake Chad, now shrunk to one tenth its original size.15 Ban took advantage of the media attention of his office to continually draw awareness to the impending challenge of global warming and climate change. He organized conferences, high-level panels, and meetings with Member States to keep climate change high on the UN’s agenda. He encouraged countries to agree on limits to greenhouse gas emissions at the international conference in Copenhagen in 2009. When that meeting failed to produce an agreement, Ban continued his efforts by meeting regularly with world leaders, ultimately culminating in the Paris Agreement of December 2015.

Another top priority for Ban Ki-moon was support for the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and he encouraged Member States to contribute to their achievement by 2015. “When we were approaching 2015 by which time the MDGs would come to an end, in 2010, I convened a summit meeting. . . . we were looking beyond 2015 for what kind of development vision we could have after the MDGs were over.”16 In 2012, at the Rio Plus 20 summit, he explains, “We created a basic framework which later was developed into the Sustainable Development Goals [SDGs], the 2030 Development Agenda.”17 Ban did not want to lose the momentum mobilized by the MDGs and made sure the global community kept moving forward on development. The SDG’s seventeen goals are more complex but visualize development in a more holistic manner. Ban was determined to involve the Member States in the process so they would feel ownership in the process and dedication to their success.

Ban Ki-moon was also concerned about gender equality and the empowerment of women. He immediately began to be more proactive about appointing women within the Secretariat at the political level where the Secretary-General has the authority to select candidates. “The selection committees were composed of men,”18 Ban complained, and told his advisers he wanted to see more female candidates, demanding “the next time I would like to see that the three finalists would include a woman, at least one woman.”19 In this way, he set a new standard for moving more women into top positions. In 2010, the General Assembly passed a resolution approving his proposal to create UN Women and he appointed Michelle Bachelet—former president of Chile, whom he had met while visiting Antarctica—to head the new body.20 He launched a number of initiatives in support of women’s rights and created Unite to Fight Against Violence Against Women, but also realized it was important to change the mentality of men. To that end, he initiated the Male Leaders Network that included global leaders like Archbishop Desmond Tutu and Prime Minister Zapatero of Spain. In connection with UN Women, Ban began Every Woman, Every Child, a campaign focused on human rights and health. And in welcoming in the social media era, in 2014, he created the HeForShe campaign and asked actress Emma Watson to be his Global Ambassador for Women.21

During his term, Ban became aware of sexual violence that had taken place in UN missions by soldiers and other UN personnel as reported in the media and began a No Tolerance campaign. He took these violations very seriously and believed that the perpetrators should be held accountable. “I reported to the UN Security Council that. . . . It was not just enough to punish those who had committed the crimes. So, I made the rule that depending on the seriousness of the crimes, I would ask the responsibility to fall on the officers in command.”22 After a set of serious crimes of sexual violence had taken place in 2015 in the Central African Republic, Ban called for the resignation of the head of the UN mission there. He knew from his own experience as Korea’s vice foreign minister, when an important line has been crossed, those in charge must take the responsibility.

Ban Ki-moon is also known for his support of the LGBTQIA+ community and was heavily criticized by people who do not support LGBTQIA+ human rights. He explains, “All human beings are born equal, and with equal rights and equal opportunities. Simply, they have a different sexual orientation.”23 Ban made it clear that every staff member would be treated equally. Within the Secretariat, regardless of sexual orientation, everyone’s rights to family allowances, opportunities, and personnel benefits would be honored. He had a hard time with some in the General Assembly who wanted to deny these equal benefits because of policies of discrimination in their home countries, but he fought to save these rights and won. He explains, “I was threatened, you know, politically [but] I was very grateful to many Member States who supported my policy.”24

Every Secretary-General is faced with the challenges of war and conflict in various parts of the world, as well as myriad other global events that threaten lives. Ban Ki-moon took this responsibility very seriously and worked to resolve issues through the use of his “good offices” to mediate for peaceful solutions. He traveled and met with leaders to try to convince them to choose the path of peace in all situations. In Darfur, he successfully convinced Sudan’s leadership to allow UN peacekeepers to join and strengthen the African Union’s efforts to protect thousands of civilians who were displaced and suffering due to conflict. In 2007/2008 when violence threatened the peace in Kenya, Ban fully supported the African Union’s endorsement of Kofi Annan to mediate an agreement and flew to Nairobi to give the UN’s full backing to the Annan effort. When Syria erupted and the Security Council was unable to take action, the UN General Assembly stepped in and asked Ban to name a special envoy to seek a peaceful settlement; he named Kofi Annan. In 2013, evidence emerged that the Syrian government was using chemical weapons against its people. Ban launched an investigation and sent a team to Damascus. When the team was fired upon, he encouraged them not to be intimidated and to continue their work. Their report led to the UN overseeing the elimination of Syria’s chemical stockpiles and delivery systems.

Ban Ki-moon also stepped in when natural disasters occurred. In 2008, Cyclone Nargis swept through Myanmar causing widespread damage and devastation. Myanmar’s military junta announced they would not accept any assistance from the outside world. “At that time,” Ban explains, “Foreign Minister Kouchner of France was suggesting that the Responsibility to Protect be applied.”25 First introduced in 2001, the Responsibility to Protect is a normative concept created to address humanitarian crises when the host country is unable or unwilling to act. The Myanmar leadership was afraid the UN would forcibly send peacekeeping troops as a mandate in the name of humanitarian intervention. However, they were willing to accept a visit by the UN Secretary-General, so Ban immediately flew to Myanmar to meet with the leadership. With deference and diplomatic skill, he convinced them the UN was an impartial entity and was only there to help. He immediately held a donor’s conference and ultimately, humanitarian aid was allowed into the country.26 Despite these efforts, Ban was heavily criticized in the media for not demanding to meet with Noble Prize Laureate Aung San Suu Kyi. He graciously accepted the criticism, but knew he had to balance such a meeting with providing humanitarian aid to those suffering from the consequences of the cyclone. Had he demanded to see Aung San Suu Kyi, that door would have been closed. However, Ban was able to meet with her at a later date.

Ban Ki-Moon at the United Nations in NYC in 2007

Another disaster erupted in 2010 when a devastating earthquake struck Haiti, toppling buildings and killing or injuring many Haitian citizens. The UN headquarters in Haiti also collapsed, causing the deaths of several UN personnel including the head of the UN mission, Hedi Annabi. In the follow-up to the earthquake, a cholera epidemic broke out due to the serious neglect of proper sanitation by UN peacekeepers. The disease spread quickly, killing some 9,000 people.27 The UN was subjected to heavy criticism for being the source of the epidemic and was further blamed for not accepting the financial responsibility. Ban Ki-moon, as the symbol of the UN, took the brunt of this anger. The UN legal team had responded by invoking the immunity of the Organization from lawsuits, which was held up by United States courts. With its exposure all over the world and very limited annual budget, the UN would not be able address this kind of financial burden. It was not until 2016 that the UN reached a solution. Ban Ki-moon apologized to the Haitian people and announced he had established a voluntary fund of $400 million to address the needs of Haiti and provide assistance for those most affected by the epidemic.28

When asked about the UN’s relationship with the media, Ban Ki-moon responded, “It is critically essential. . . . Why? Because in this world, the media can play a connective role between the United Nations and governments and people in the world.”29 He explained that without the media, his voice, his message, would just stay within the walls of UN headquarters.

This is a brief sketch of the life and work of Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, offering a few selected highlights of his life, entry into geopolitics, and events that transpired during his time as Secretary-General of the United Nations. His two terms as Secretary-General spanned ten years and witnessed numerous violent conflicts, massive migration of people fleeing deprivation, and the human consequences of natural disasters, all of which placed enormous demands on UN resources. But also in that time, governments from around the world, with the support of the UN and civil society, came together to hammer out the Paris Climate Agreement and continued addressing the needs of those most vulnerable through advancing the Sustainable Development Goals. For Ban Ki-moon, support for human rights is essential. He explained that while the UN must remain impartial, at the same time, “It cannot be neutral. . . . I have to criticize the perpetrators and I have to protect the human rights’ principles. . . . We have to speak out.” His final message to his successor was that the United Nations must continue to have compassion for the millions of “people who need our urgent humanitarian assistance.”30

Notes:

1. Ban Ki-moon biography – life, family, children, history, school; found at www.notablebiographies.com, page 1; accessed October 2019.

2. Interview with Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon on December 28, 2016, at the UN in New York, by Jean Krasno, page 1.

3. Ibid, page 2.

4. Ibid.

5. Interview with Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon on October 22 , 2018, at the Kennedy School, Cambridge, MA, by Jean Krasno, pages 1 and 2.

6. Ibid.

7. Ban Ki-moon biography, www.notablebiographies.com, page 1.

8. Interview with S-G Ban Ki-moon on December 28, 2016, page 2.

9. Ban Ki-moon biography – life, family, children, history, school; found at www.notablebiographies.com, page 1; accessed October 2019.

10. Interview with Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon on October 22 , 2018, pages 8 and 9.

11. Ibid.

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14. Ban Ki-moon, Statement on Antarctica, November 9, 2007, United Nations, Secretary-General’s statements.

15. Interview with Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon on December 28, 2016, page 3.

16. Ibid, page 4.

17. Ibid.

18. Interview with Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon on October 22 , 2018, page 4.

19. Ibid.

20. Ibid, page 6.

21. Ibid, page 7.

22. Ibid, page 8.

23. Interview with Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon on December 28, 2016, page 5 and 6.

24. Ibid.

25. Interview with Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon on June 8, 2017, in New York by Jean Krasno, page 3.

26. Ibid, pages 1-5.

27. “New UN System approach to Cholera in Haiti,” www.un.org, December 2016.

28. Carol Gaensburg and Ronald Cesar, “UN Fund to Fight Cholera in Haiti Hovers at 2 percent of goal,” VOANews/the Americas, March 1, 2017.

29. In person interview with Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon on May 2, 2022, in New York City by Jean Krasno.

30. Interview with Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon on December 28, 2016, page 10.