MASS CULTURE

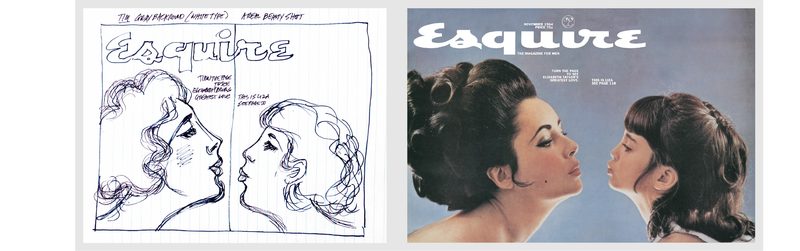

Elizabeth Taylor, iconic Hollywood starlet, achieved meteoric fame in the 1960s for her powers of seduction both on and off the screen. Over the course of her life Taylor was married eight times to seven different men. Her most notable love affair was with debonair actor Richard Burton, whom she fell in love with on the set of the epic 1963 film Cleopatra. A year after filming, both actors left their spouses to marry (only to divorce, then later remarry in 1974). Their union sparked a media frenzy that cemented Taylor’s legacy as a notorious femme fatale. Eager to satirize the public’s tawdry appetite for gossip and scandal, Lois conceived of a fold-out cover that would reveal Taylor’s greatest love once and for all: her daughter, Liza. Providing yet another twist on Esquire’s preferred “girlie” covers, Lois’s composition conveys Taylor’s magnetism and independence in equal measure, qualities that the ad man himself epitomized in his work with the magazine.

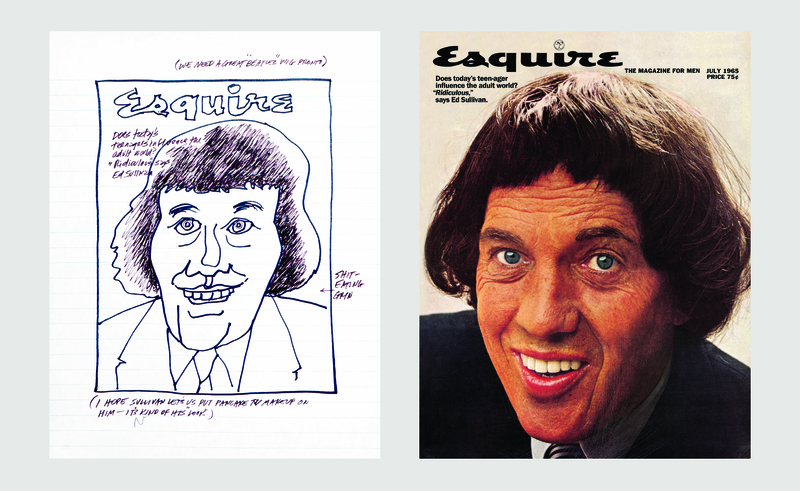

Over the course of its 23-year tenure on television, running every Sunday night on CBS between 1948 and 1971, The Ed Sullivan Show shaped the trajectory of pop culture in the United States. Catapulting Elvis Presley to stardom after his 1956 debut on the show, Ed Sullivan made history again in 1964 when he was the first to introduce The Beatles to American audiences. One year later, when Lois was tasked with creating a cover for Esquire’s upcoming issue on the cultural influence of teens, he lit upon the ironic idea to pose Sullivan, a 63-year-old tastemaker, as a wannabe teenager wearing a Beatles wig and a “shit-eating grin.” The resultant image is both comical and telling: nothing has a greater impact on pop culture than the mass media and the men who run it.

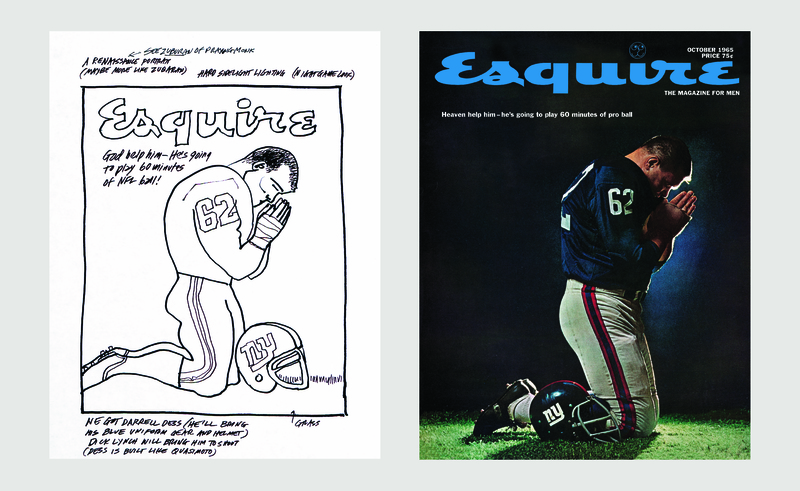

Drafted for an issue devoted to sports writing, Lois’s October 1965 cover offered a prescient glimpse into the intersection of two of America’s greatest passions: football and faith. The design features Darrell Dess—a pugnacious player for the New York Giants—on his knees in prayer before a primetime night game. Spotlighted from behind to create a halo effect, Dess’s genuflection aligns him more closely with the devotion of saints in Renaissance paintings than the aggression of his offensive linemen contemporaries. Lois intended the cover to mock the pervasion of religion in sports, in particular the presumption that God would deign to support the home team instead of solving the world’s countless ills. Today, however, as the critical, long term effects of concussions become ever clearer, the image reads less like a misguided appeal for victory than a desperate prayer for safety. As Lois later explained, “In sixty minutes of professional football a man could get killed.”

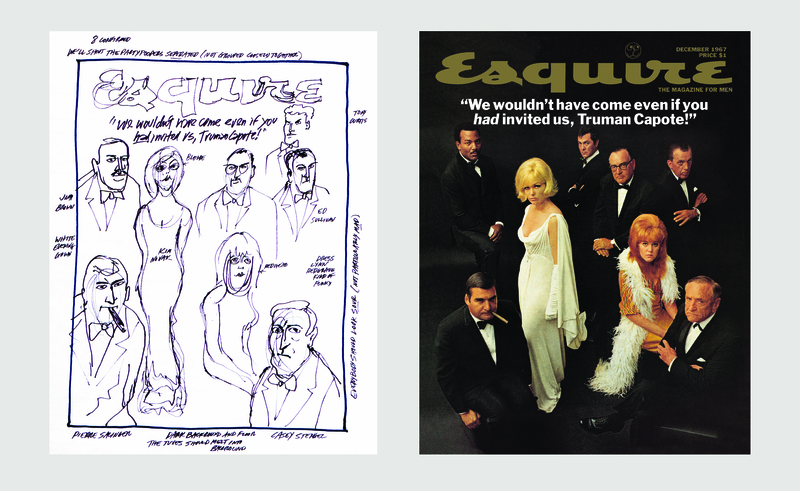

On November 28, 1966 author Truman Capote hosted a masquerade ball at New York’s Plaza Hotel for 540 of the nation’s richest and most famous public figures, including singer Frank Sinatra, artist Andy Warhol and actress Mia Farrow. Although Capote hadn’t published work in years, he remained a devoted socialite. His high-brow party captured the imagination of the mass media; The New York Times even published a complete guest list, prompting controversy over the A-listers that had not been invited. A year later, Esquire wrote a feature article on the gathering as part of a special section on “Galas, Levees, Soirees and Happenings” and Lois was assigned its cover. The resulting image mocks Capote’s trivial cause célèbre by gathering eight rejected celebrities in their black tie best for a party all their own. Feigning sour expressions and social superiority, the famed figures become fodder for Lois to lampoon the petulance and puerility of modern day celebrity.

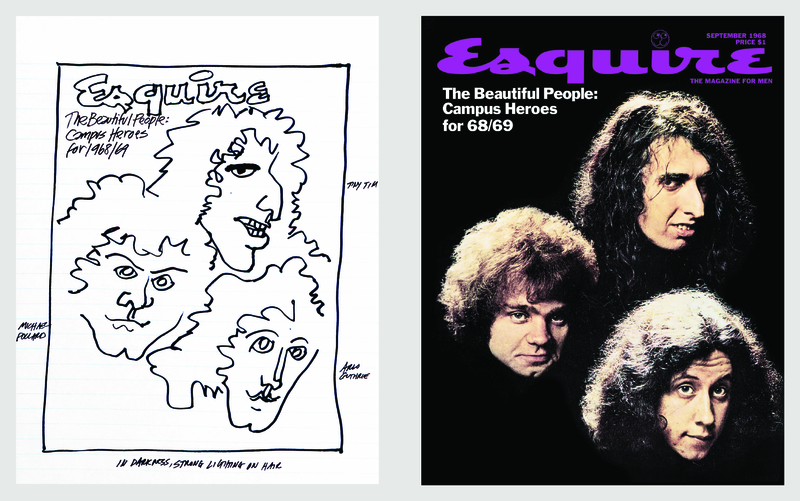

America’s seven million college students (and the untapped readership demographic they represented) inspired much of Esquire’s content in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Crafted for an issue on youth and revolution, Lois’s September 1968 cover turned three “campus heroes”—singer Tiny Tim (top), actor Michael J. Pollard (center) and singer-songwriter Arlo Guthrie (bottom)—into unlikely cover stars. Though not your typical “beautiful people,” this trio maintained an outsized influence over young adults across the nation. By cropping out their bodies to focus on their long, unruly hair and ordinary faces, Lois captures the democracy, accessibility and freedom at the core of the countercultural revolution.

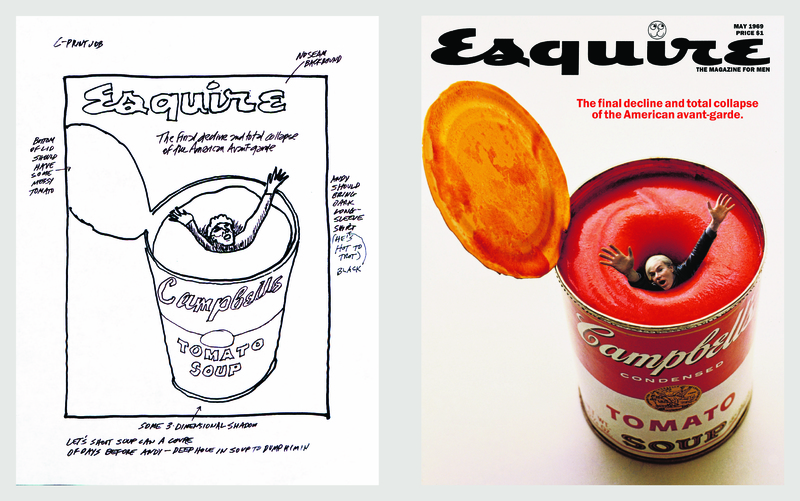

In 1962 Andy Warhol created a series of odd, deadpan artworks the likes of which the public had never seen when he painted 32 realistic “portraits” of Campbell’s Soup cans. The paintings marked the beginning of the Pop Art movement, which inserted commercial imagery into fine art, and helped skyrocket Warhol to international success. More than just an original thinker, however, Warhol boasted an outlandish personality that captivated the public’s imagination, allowing him to transcend the art world to become a true cultural icon. Lois’s cover, responding to an article on the “collapse of the American avant-garde”, parodies Warhol’s gleeful complicity in art world apocalypse by depicting him drowning in one of his characteristic Campbell’s cans. Branding the artist a willing victim of his own success, the image was achieved through painstaking photo splicing and remains one of Lois’s most revered Esquire covers of all time.

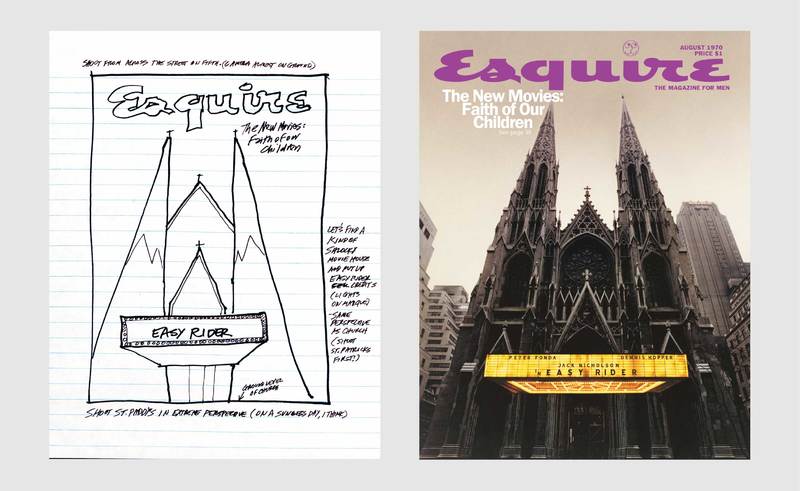

With this controversial, sacrilegious cover, Lois sought to homogenize an issue that broadly dealt with youth culture in America. One year earlier Dennis Hopper’s coming of age film Easy Rider became a runaway hit among young audiences who, like the movie’s main characters, found escape from the nation’s social and political problems through drug use, camaraderie and “free love.” Emphasizing the conflicting devotions among America’s various generations, Lois attached a garish movie marquee to the facade of New York’s towering St. Patrick’s cathedral. The result was a cover that celebrated the trend toward “heathenism” by suggesting that mass culture—as emblematized by films like Easy Rider—might serve as the new moral center for today’s youth.