POLITICS

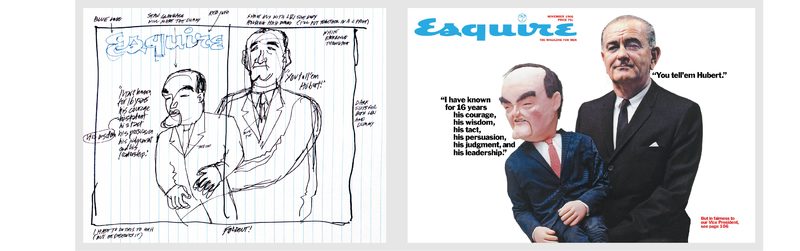

There is perhaps no better indication of Lois’s exceptional talents than the unparalleled leeway that Esquire editor Harold Hayes granted the ad man in dictating the content and composition of his covers. Often, as evidenced by several examples in this gallery, Lois’s designs directly contradicted the argument of the article he was highlighting. Such was the case with the November 1966 cover depicting then Vice President Hubert Humphrey as a ventriloquist's dummy mimicking President Lyndon B. Johnson’s stance on the war. Only after Lois had commissioned the unflattering Humphrey dummy, carefully spliced LBJ’s photo onto a model’s body, and conceived of the sycophantic quotes did he discover that Esquire was running a positive profile on the VP. Hayes, however, could not bare to scrap the clever cover and compromised by hiding the aside “In all fairness to the Vice President . . .” in the fold out.

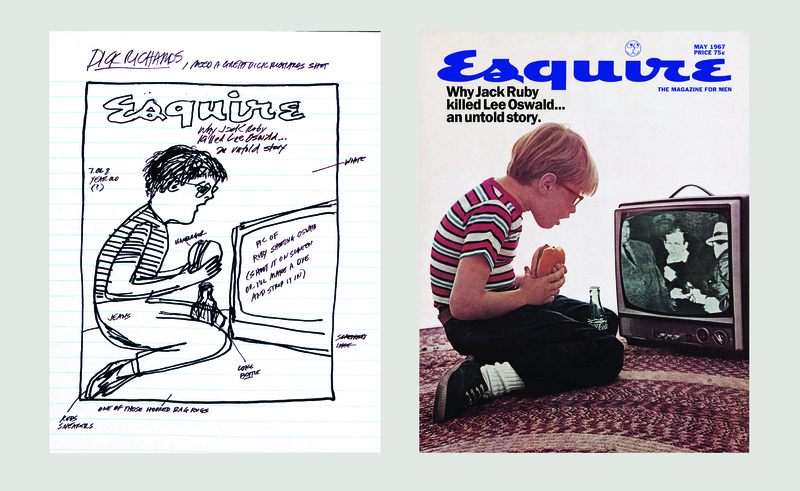

Many of Lois’s covers reached beyond the printed page to consider the changing effects of popular culture on other mass communication vehicles, including music, film, literature and television. By the late 1960s the ramifications of America’s postwar economic and technological advances were plain: every middle class home had a television and that small electrified box could transport the latest disaster directly to your living room. This fact proved devastatingly clear on November 24, 1963 when Jack Ruby murdered John F. Kennedy’s alleged killer, Lee Harvey Oswald, on national tv while millions of people, young and old, watched in horror. Accompanying Esquire’s “untold story” behind the Ruby slaying, Lois’s cover captures the picture of American innocence—a blond, bespectacled boy on a rag rug, wearing jeans and dirty sneakers, holding a coke and hamburger—shattered by a firsthand view of extreme violence.

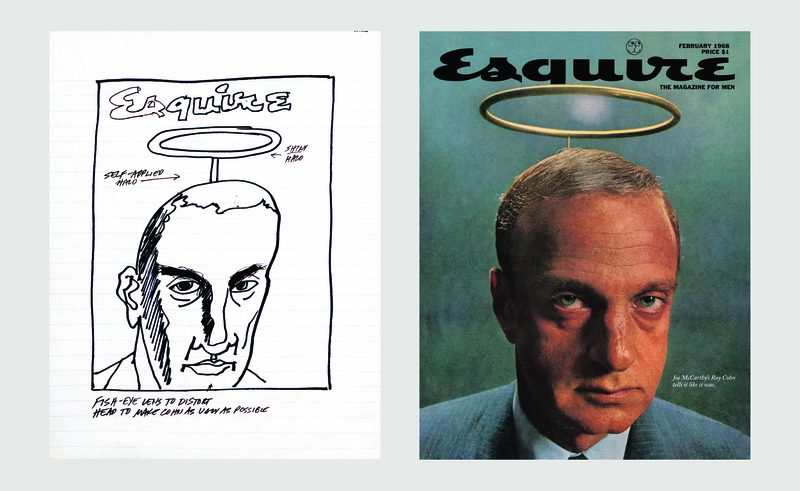

A “Red Scare” swept through American politics in 1953 when Senator Joseph R. McCarthy began a systematic campaign to root out suspected Communists in the United States government. Now widely considered a fallacious witch hunt, McCarthy was assisted in his investigations by Roy Cohn, a New York attorney who had successfully prosecuted Soviet spies and, before eventually being disbarred, would later go on to serve as legal counsel for Donald Trump. In 1954, when McCarthy’s machinations started to crumble, Cohn was forced to resign and return to the private sector. Over a decade later Esquire decided to publish a portion of Cohn’s forthcoming book detailing his experience of the congressional hearings that led to his downfall. To “honor” the lawyer’s return to grace Lois convinced Cohn to don a halo, adopt a brooding glare and stand before an unflattering camera lens. The obvious falsity of the resulting cover image perfectly parodied Cohn’s own penchant for deceiving the public.

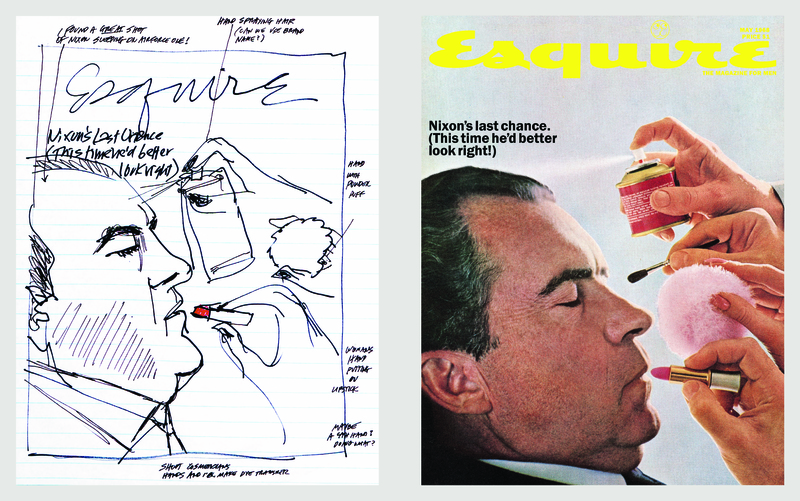

Modern American politics were forever changed on September 26, 1960 when CBS hosted the first televised presidential debate, staged between Democrat candidate John F. Kennedy and Republican candidate Richard Nixon. The importance of being able to see the orators could not be underestimated; radio listeners found Nixon’s arguments sounder but Kennedy’s telegenic good looks helped put him in the Oval Office. Eight years later, as Nixon attempted to win over the public again, Lois pinpointed the pressure facing the former Vice President to “look right” for the cameras. Created by composite, the cover depicts a seemingly comatose Nixon barraged with hairspray, eyeshadow, foundation and lipstick. Unsurprisingly, the politician’s staff was outraged by the perceived attack on his masculinity, perhaps recalling Lois’s draft dodging lipstick cover from 1966. Mocking the performative facade required of American politicians, Lois’s design presaged the deceit that would later define Nixon’s legacy in the wake of Watergate.

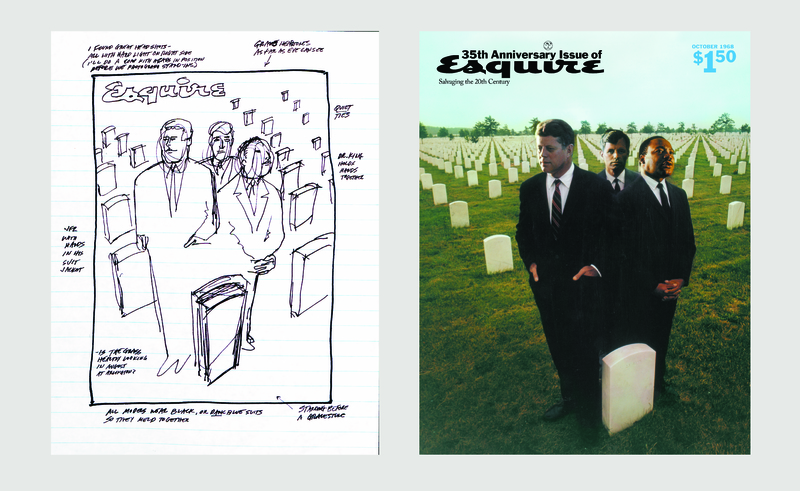

Lois’s Esquire covers continued to engage contemporary audiences, even decades after their debut, because they offered readers a unique combination of wit, impertinence and shock. Occasionally, however, an issue’s subject matter mandated a more somber, reverential approach. For the 35th anniversary issue of the magazine, themed around “salvaging the 20th century,” Lois crafted a cover that embodied the desolation and despair that pervaded the United States as the 1960s drew to a close. Following the assassinations of America’s most visionary leaders—JFK in 1963, then RFK and MLK Jr. just nine weeks apart in 1968—Lois paid homage to their public service, situating them amidst rows of tombstones at Arlington National Cemetery. A modern-day Holy Trinity, the great men watch over the countless, unnamed soldiers that also gave their life in an attempt to protect our country’s future. The cover is both poignant and pithy, mirroring the raison d’être of an anniversary issue by encouraging the viewer to contemplate their own contributions to society.