WAR

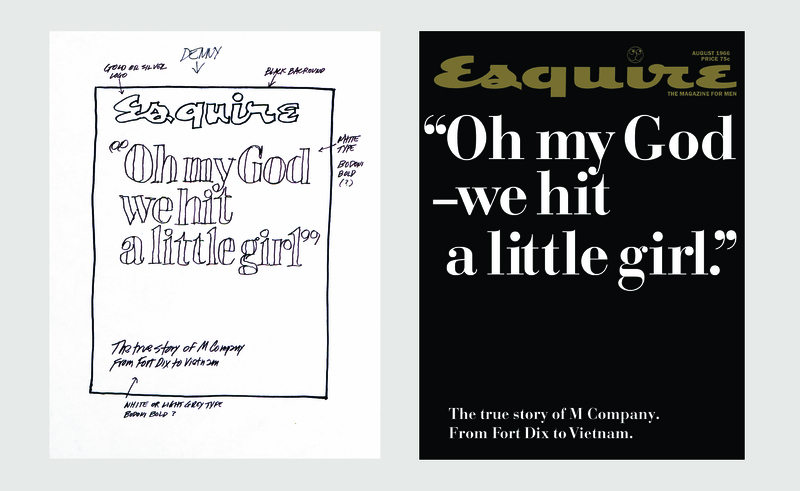

At the start of 1966 over 5,000 American soldiers had died in Vietnam and 385,000 more were still fighting. Despite these staggering numbers, those back home in the United States still remained relatively unaffected by the conflict. Thus John Sack’s profile of one army company—following its members from basic training to combat—offered Esquire readers some shocking revelations. Even so, Sack did not grasp the full ramifications of the piece, pitching a cover that mocked his subjects by portraying them as Beetle Baileys, the inept comic strip soldier, blindly jumping into the fray. Lois, conversely, seized upon the bleakness behind Sack’s story, reproducing a harrowing quote from one combatant in unmistakably stark black and white. Esquire was criticized for prematurely indicting the war, but Lois saw the writing on the wall: “The cover screamed to the world that something was wrong, terribly wrong. Good American boys were trapped in an evil war, with no end in sight.”

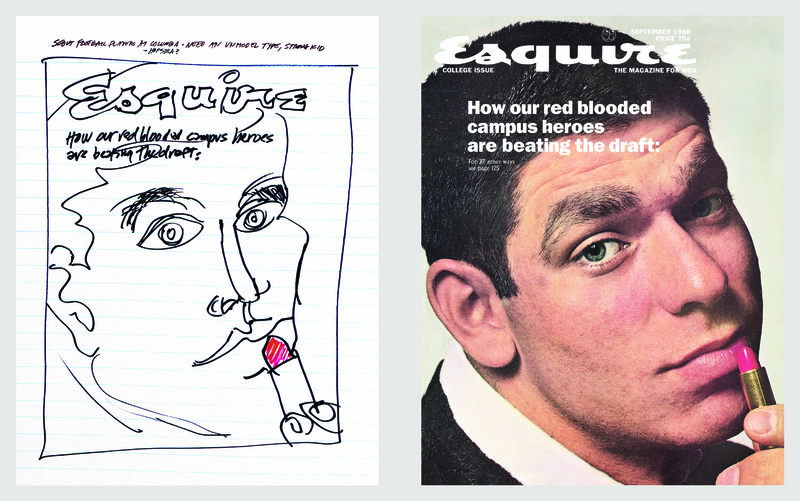

Made for the “college issue,” Lois’s second Vietnam cover coincided with a series of articles on the numerous, and often facile, ways young men might dodge the draft. Though the worst horrors of the conflict had yet to be seen, college students across America were already strongly opposed to what they saw as an irrational, unnecessary war and were desperate to avoid fighting it. In typically impish fashion, Lois lit upon an idea—that feigning homosexuality would help fail a draft test—which simultaneously lampooned the misguided conservatism of the U.S. military and its arbitrary standards for deciding who might be sent off to die. To hammer this point home, Lois recruited a ruggedly handsome Columbia University football player as his model, contrasting the athlete’s thick black hair, bushy brows and five o’clock shadow with a bright red lipstick in a seductively shiny case. Above his head Esquire’s tagline—”The Magazine for Men”—held newfound connotations.

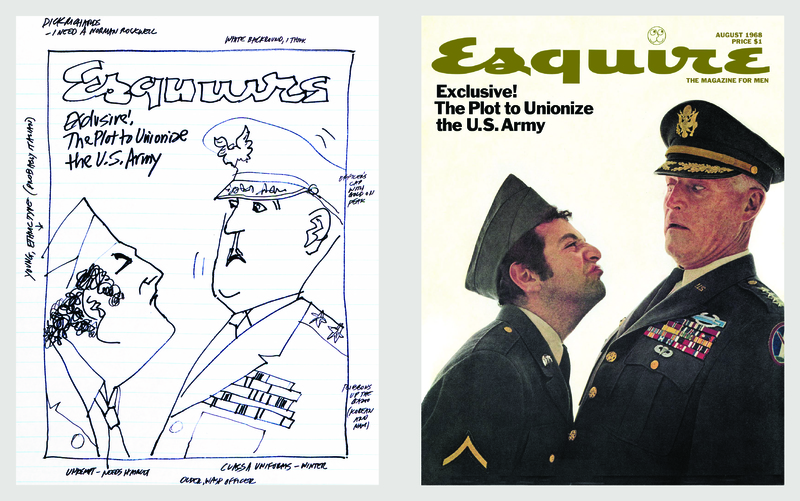

The summer of 1968 left the nation reeling from the assassinations of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr., race riots across the country, and a raging war in Southeast Asia. By August the bloody Tet Offensive was nearing its peak and student unrest was more prevalent and vocal than ever. The United States government was desperate to reestablish law and order, both at home and abroad. Amidst these tense and violent times, Esquire ran an article about Andrew Dean Stapp, a recent enlistee who—like most of America’s idealistic youth—believed in expanding civil liberties. For Stapp that meant unionizing the U.S. Army to ensure, among other things, the right to refuse illegal orders. Though Stapp’s campaign proved ultimately unsuccessful, the radical brashness of his idea inspired Lois, a drafted veteran of the Korean war, to create this parodic cover depicting an upstart GI sneering at a discomfited four star general.

Lois’s provocative covers not only encapsulated the riotous spirit of the times, but also single-handedly galvanized Esquire’s reputation as a touchstone for America’s university revolutionaries. Throughout the late 1960s, students across the country banded together to protest the Vietnam War. Their outcry was met with derision from public officials and violence from police. The result with an unshakeable generational opposition to authority, with a particular distrust of those who job it was to “serve and protect.” This cover, a faux “Freshman Orientation” packet preparing new students to the contest to come, depicts a handsome young man sinking down to a lumbering swine’s level. Lois’s design telegraphed support of the “The Kids” (America’s future) over “The Pigs” (the police establishment), garnering the magazine copious complaints from law enforcement officers alongside the unwavering loyalty of college students everywhere.

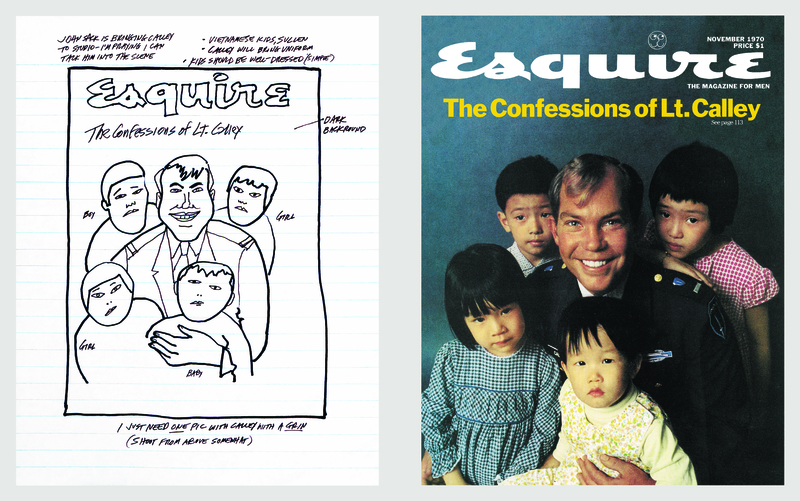

By design nearly all of Lois’s Esquire covers courted controversy, but very few instigated equal infighting with the editorial offices of the magazine itself. Such was the case with Lois’s “Killer Cover” in 1970, which featured a smirking Lieutenant William Calley—the platoon leader who supervised the 1968 “My Lai Massacre” that killed as many as 500 men, women and children—surrounded by four small, sullen-faced Vietnamese kids. The cover accompanied John Sack’s extensive interviews with Calley, published in conjunction with the start of the soldier’s court martial for 109 counts of murder. (He was convicted on 22 counts a year later, but only served three years house arrest after a Nixon pardon.) Sack’s article positioned Calley as a scapegoat, but Lois alluded to a more harrowing narrative of sadistic premeditation by surrounding the unrepentant soldier with mournful, innocent faces. Though divisive, the cover was chameleon-like enough to provide ammunition for both Calley’s supporters and detractors.